December 13, 2017 - As the tax reform process grinds on in Washington, Wall Street – and Main Street – are examining how it affects both individuals and companies. (Spoiler: There appear to be winners and losers on both streets.) This week, Moody’s published their third installment of “Debt and Taxes”, which discussed how the tax reform bill could affect different types of companies. We discuss their analysis – and companies’ reaction to the bill – below.

The Senate and the House corporate tax proposals differ, but they generally share three broad components. First, they reduce the overall corporate tax rate from 35% to 21% (at press time). Second, they permit immediate expensing of capex for a certain period of time. Third, they limit the tax deductibility of interest to roughly 30% of EBITDA in the House bill and 30% of EBIT in the Senate version.

The result is that if a company pays high taxes, has a high level of capex but not a lot of interest expense, it could see a significant reduction in its tax bill. Conversely, if a company does not currently pay a lot of tax, does not have a lot of capex but does have high interest costs, the company may see an increasing tax bill.

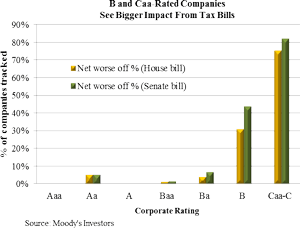

Weighing these three factors (and using the initially proposed 20% corporate tax rate), the benefits outweigh the costs for nearly all investment grade companies, Moody’s writes. But as one goes down the ratings spectrum, the benefits of a lower rate and immediate capex expensing begin to be outweighed by the limitation on interest deductibility. Under the House plan, 26% of speculative grade companies are worse off. Under the Senate plan, which is more punitive because interest is assessed against EBIT rather than EBITDA, 36% of speculative grade companies are worse off. But as is illustrated in the LSTA’s Chart of the Week,  the impact on speculative grade companies is concentrated in B rated entities (31% worse off under House bill, 44% worse off under Senate bill) and Caa-C rated entities (76% and 82%, respectively).

the impact on speculative grade companies is concentrated in B rated entities (31% worse off under House bill, 44% worse off under Senate bill) and Caa-C rated entities (76% and 82%, respectively).

Importantly, while most companies benefit today from the tax bill, pressure could ratchet up in less benign environments. Today, EBITDA growth is solid and interest rates are low. If interest rates – and thus interest costs – rise faster than earnings, more companies may see their interest costs pierce the 30% EBIT/EBITDA level. In addition, in a recession, the new tax bill might bite. If earnings decline, interest will comprise a larger percentage of EBIT/EBITDA. Thus, in a downturn, a company’s cash tax burden might not decline as much as expected. Moody’s notes that some companies could even find themselves having a positive cash tax burden but negative free cash flow.

Then there’s the impact on the LBO model. Most LBOs are rated B2 or B3; 27% of B2 rated companies are worse off under the House bill, while 41% are worse off under the Senate bill. For B3 companies, the numbers are 50% and 63%, respectively. More specifically, 66% (House) and 93% (Senate) of single-B issuers will lose the ability to deduct at least some part of their interest expense. On the flip side, lower tax rates should provide the most benefit to large publicly traded companies, Moody’s adds. The increased cash flow for public companies could allow them to bid more aggressively for acquisition targets. This combination theoretically could lead to higher purchase price multiples and more costly debt. Not an ideal combination for LBOs.

So how are companies responding? Cautiously. Thomson Reuters LPC wrote that a number of leveraged companies, including sensor supplier MTS Systems, and retailers JC Penney and Floor & Décor, have warned investors that changes in interest deductibility could impact their results. More directly, the CEOs of Dell Computer, Dow Chemical, S&P, First Data and Discovery came together to publish an op-ed in The Hill. The CEOs applauded the tax cut, but raised concerns about the limitations on interest deductibility. They noted that interest expense is a normal cost of business and deductions have been ingrained in the U.S. tax code for roughly a century. In turn, a sudden change in this policy could punish businesses that made debt-financed investments in good faith. So, the CEOs urge, if the limitation on interest deductibility plank is not eliminated, at the least it should be eased. They suggested using the House EBITDA method, they recommended exempting existing debt from the new bill – or at least phasing the elimination for existing debt over several years.

The LSTA will continue to track this issue, which has implications for leveraged borrowers and the leveraged loan market.